Particle in a ring

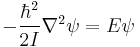

In quantum mechanics, the case of a particle in a one-dimensional ring is similar to the particle in a box. The Schrödinger equation for a free particle which is restricted to a ring (technically, whose configuration space is the circle  ) is

) is

Contents |

Wave function

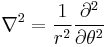

Using polar coordinates on the 1 dimensional ring, the wave function depends only on the angular coordinate, and so

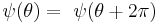

Requiring that the wave function be periodic in  with a period

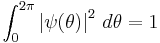

with a period  (from the demand that the wave functions be single-valued functions on the circle), and that they be normalized leads to the conditions

(from the demand that the wave functions be single-valued functions on the circle), and that they be normalized leads to the conditions

,

,

and

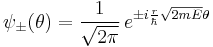

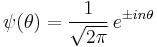

Under these conditions, the solution to the Schrödinger equation is given by

Energy eigenvalues

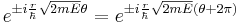

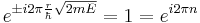

The energy eigenvalues  are quantized because of the periodic boundary conditions, and they are required to satisfy

are quantized because of the periodic boundary conditions, and they are required to satisfy

, or

, or

The eigenfunction and eigenenergies are

where

where

Therefore, there are two degenerate quantum states for every value of  (corresponding to

(corresponding to  ). Therefore there are 2n+1 states with energies up to an energy indexed by the number n.

). Therefore there are 2n+1 states with energies up to an energy indexed by the number n.

The case of a particle in a one-dimensional ring is an instructive example when studying the quantization of angular momentum for, say, an electron orbiting the nucleus. The azimuthal wave functions in that case are identical to the energy eigenfunctions of the particle on a ring.

The statement that any wavefunction for the particle on a ring can be written as a superposition of energy eigenfunctions is exactly identical to the Fourier theorem about the development of any periodic function in a Fourier series.

This simple model can be used to find approximate energy levels of some ring molecules, such as benzene.

Application

In organic chemistry, aromatic compounds contain atomic rings, such as benzene rings (the Kekulé structure) consisting of five or six, usually carbon, atoms. So does the surface of "buckyballs" (buckminsterfullerene). These molecules are exceptionally stable.

The above explains why the ring behaves like a circular waveguide, with the valence electrons orbiting in both directions.

To fill all energy levels up to n requires  electrons, as electrons have additionally two possible orientations of their spins.

electrons, as electrons have additionally two possible orientations of their spins.

The rule that  excess electrons in the ring produces an exceptionally stable ("aromatic") compound, is known as the Hückel's rule.

excess electrons in the ring produces an exceptionally stable ("aromatic") compound, is known as the Hückel's rule.